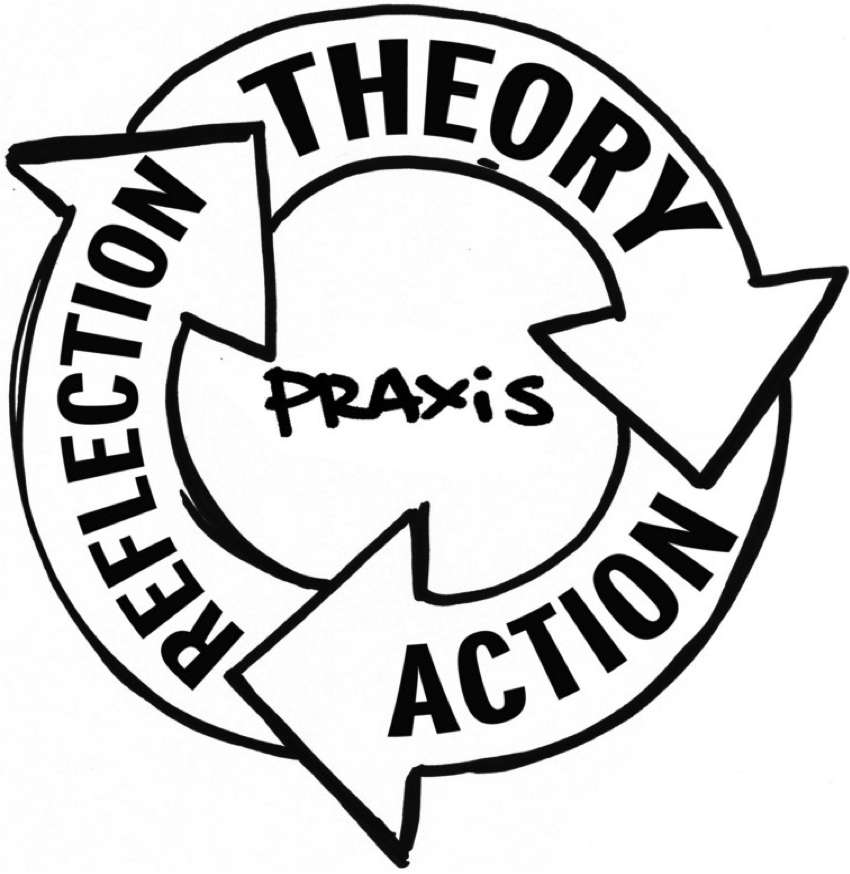

The Praxis Wheel. Art by Joshua Kahn Russell

Over the last few years I have been traveling the world advising large companies on how to implement lean innovation methods within their companies. This work has led me to run innovation workshops, design innovation frameworks, work with management team on strategy and coach product teams in great organizations like Pearson, Airbus, Josera, Standard Bank and The British Museum. These experiences are informing the book I am currently writing with Dan Toma entitled The Corporate Startup.

I love my work, but almost inevitably in every company I have worked with, discussions will at some point get heated. Lean innovation requires cultural and mindset shifts that are often experienced as counter-intuitive by leadership in many large organizations. As our conversations get to boiling point someone in the meeting will inevitably say something like:

- “What we do here is not academic. This is a real business, not theory”.

- “We need practical people in this business, not academics like you. You are too academic to succeed in business”

Now. I will admit. I am an academic. I have two masters degrees and a PhD in Psychology. One of my master degrees is an MBA. I taught at University of Kent in UK for over 12 Years; and am now adjunct faculty there. But I can guarantee you that all of these fancy accolades have nothing to do with the price of tea in China or whether I bring value into any conversation. And yet it has become a stick that people use to beat me with. Especially, when they want to resist the change that lean innovation requires. I am discredited for having spent so much time in the academy. Ignore these theoretical types, they say. Practice trumps theory!

And so this is my rant… No no no. Practice does NOT trump theory. And also there are other reasons why calling me too academic may not be the insult that people think it is. There maybe more reasons but I will outline my top three reasons below:

- Academic ≠ Armchair Philosopher

The use of the word ‘academic’ by most people reveals a lack of understanding of what really happens in academic institutions. There is a myth that academics are all armchair philosophers, who sit around making stuff up. The misconception here is that academics don’t base their work on real world best practices. And this is wrong. It is so very wrong.

The vast majority of academics are researchers. And by research, I don’t mean what you did when you were preparing term papers in college (i.e. read books and articles). Academic research consists mostly of the collection of real world data in search of underlying causes, repeatable patterns and things that work in real life contexts. In business for example, this sometimes involves studying decision making and management processes in companies that succeed versus fail at sustained innovation. And most of what academics learn is counter-intuitive.

Jim Collins’ research that informed his seminal book Good to Great, produced the counter-intuitive finding that it is not charismatic leaders that create great companies but the understated almost invisible leaders that lead with humility. Clayton Christensen’s work on disruptive innovation has shown that great companies get disrupted when they focus too much on their most profitable customers and deliver products that meet their needs. This is completely counter-intuitive and helps management make different sorts of decisions.

We can of-course debate the veracity of the research and some of the conclusions reached on the basis of the data. This is what happened most recently in a New Yorker article by Harvard Professor Jill Lepore that challenged Christensen’s work. This is of-course healthy and happens in the academy quite a bit. But it is NOT armchair philosophy. Clayton Christensen, Rita McGrath, Jim Collins and others are not sitting around making stuff up.

The role of the academy, from history and psychology to geography and medicine; and also business studies is to look for causal patterns of how things work and then share it with the world. This data is collected in the real world using various methods (e.g. the case study). And when the knowledge is shared with business leaders, if they dismiss it as being too academic they are missing the point.

2. Uninformed Practice is Garbage

Practice that is not informed by knowledge is actually theorizing disguised as practical. Think about that for a minute. The insinuation that I am too academic is based on the assumption that I am making up untested theories. And if I am then this is wrong. So why do companies view making up untested practices as good. This is totally backwards!

If your company has been engaged in the same practices for several years and you are still struggling with innovation, wouldn’t you want to know what really works? No… Yes… No… In my experience most companies are schizophrenic about this. They only want to know what works to the extent that it confirms that what they were doing was right all along! I often cringe when I hear managers say stuff like: “So, this lean innovation method is not really going to change how we work here”. Oh. Yes. It. Is.

As an example, most managers who invest in R&D want to know how much the competition is also investing. How much do they spend? What proportion of their revenue etc? But they are asking the wrong questions. A 2014 report by Barry Jaruzelski and colleagues from Strategy&, showcases ten years of research that shows that there is no statistically significant relationship between R&D spending and sustained financial performance. This finding applies to total R&D spend, as well as R&D spending as a percent of revenues. Spending on R&D is not related to growth in sales or profits, increases in market cap or shareholder returns.

It is more important that companies have an innovation framework that allows them to do things the right way. Its not really about the exact amounts of money spent. If I tell management about this research and they dismiss me as being too academic, are they being practical?! Of-course not! Uninformed practice is ultimately impractical. The “we are running a real business here” argument is garbage. You just been informed about what works in the real world and you have dismissed it because I have PhD. By the way, I never thought that I would ever write that last sentence!

3. Let’s See What Sticks

Uninformed practice is the same as saying, “…lets just try it and see what happens”. As Eric Ries rightly points out, when you do that you will be successful, but only at seeing what happens. This is because even if something sticks, your team won’t learn anything because nobody knows why it stuck. This is one of the core reasons innovators don’t learn. How can you learn anything when you run a practical test without first developing a theory of what you expect to happen.

There is myth making about the power of having done something before. I have a particular disdain for people that say that they have done something before all the time. First of all, one can always get better. But more importantly, having done something before is irrelevant if you did not learn the underlying principles that resulted in whatever success you achieved. It is even more dangerous when you assume you have learned something and your conclusions are wrong. It is equally dangerous to assume that whatever you learned in your last job applies to the current new situation — lock, stock and barrel.

In 2013, researcher Julian S. Frakish and colleagues published an amazing paper on entrepreneurial learning. They examined data from 6671 new companies. They assessed whether these new firms had been founded by people who had started companies before. They then checked whether or not previous business ownership predicted the success of these new firms. They found that previous business ownership had zero correlation to the success of new ventures. People who had never started a company where as likely to succeed or fail as those who had previously started a company.

Why might this be the case? Well it is possible that the entrepreneurs don’t really learn, they just tell us they do? (Which by the way is the title of the paper by Frankish et al.). If you start your business without making explicit the assumptions you are making and then testing them deliberately, you have experience running a business for sure, but you haven’t learned a thing. This is the power of theorizing. In academic circles we don’t theorize for the fun of it. We theorize so we can identify untested hypotheses and then run studies to test them. The theory also provides a frame of reference for interpreting data and the theory is modified if the data fails to support some of its assumption.

Another problem with assumed entrepreneurial learning is that there is tendency to think that what worked in a previous venture will also work in a new venture. This is why large companies struggle with innovation, they tend to apply the same methods and tools they use to run their core business to their new ventures. Companies need a clear theoretical view about why things work in the current venture. They then need to test whether those assumptions apply to their new ventures. This is not academic. It is 100% practical!

The Only Trump is the Donald

Practice doesn’t trump theory. Theory doesn’t trump practice. This is another one of those false dichotomies that people use in order to support whatever agenda they want to pursue. Every academic scholar will not get better unless they understand the real world practice of whatever they are studying. Similarly, every practitioner will not get better unless they understand the principles that underlie and inform their practice. This is what made Bell Labs great. It was the cross-functional mix of academics and practitioners, collaboratively learning from each other and working to make the world better.

To conclude, I will leave you with this beautiful quote from Joshua Kahn Russell that summarizes my rant is much better words :

Theory without action produces armchair revolutionaries. Action without reflection produces ineffective or counter-productive activism. That’s why we have praxis: a cycle of theory, action and reflection that helps us analyze our efforts in order to improve our ideas.