This article is the final draft of an earlier draft that I published to test out a unified framework combining McKinsey’s three horizons and Christensen Theory of Disruptive innovation. You can can find the original article here. Many thanks to those who gave feedback and helped me to refine my thinking.

Elsewhere I have argued that large companies are not startups and neither should they strive to be. Instead, large companies should view themselves as portfolios or ecosystems of products and services. The distinction between searching and executing provides a powerful lens for building that innovation portfolio. A company can use this lens to assess which of its products have validated business models and are mostly in execution mode; versus new products that are still searching for profitable business models.

The aspiration is to have a balanced portfolio of products so that when a shift happens, the company is already engaged in a systematic process of searching for new advantages, while sustaining current its cash cows and winding down declining businesses. But how can a company actively build an innovation portfolio? There are frameworks that can help us put this idea on a more rigorous footing.

Innovation Ambition

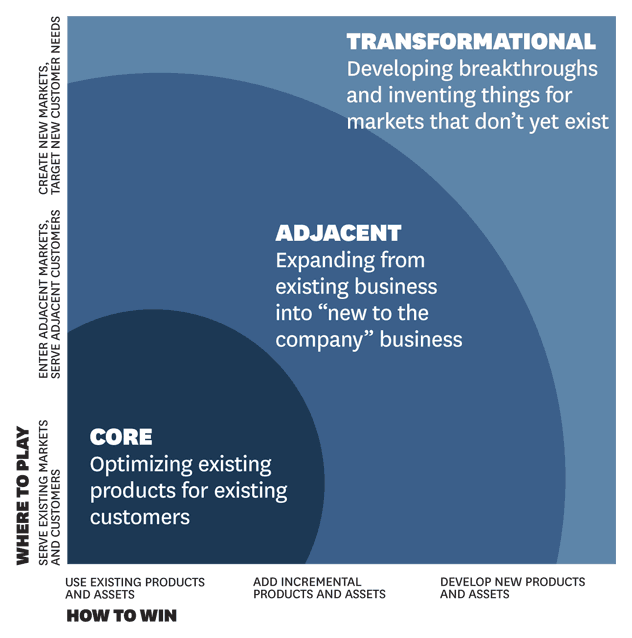

One of my favorite innovation frameworks is Nagji and Tuff’s Innovation Ambition Matrix. Their framework is an adaptation of Ansoff’s Matrix and is based on two main dimensions; products (new products versus existing products) and markets (new markets versus existing markets). Rather than use the binary distinctions that Ansoff uses in his matrix, Nagji and Tuff use a range of values. On the basis of the above two dimensions they distinguish three main types of innovation: core, adjacent and transformational.

- With core innovation company efforts focus on making incremental changes to existing products for existing customers. This can be in the form of new packaging, small redesigns of products or improvements in service. The important point here is that these innovations draw on assets the company already has in place and customers that they already understand well. These are the typical optimizations and improvements that most large companies are very good at.

- With adjacent innovation the company takes something it currently does well and applies it to new markets or to the development of new products for current markets. The point here is that the company is drawing on existing capabilities and putting them to new uses. The entry of adjacent markets and the development of new products using current capabilities can be a stretch; but it is not typically out of reach for many large companies.

- In contrast, transformational innovation focuses on creating new offerings for new markets. In this situation, the company often has to develop new capabilities, products or services, while simultaneously testing these offerings in new markets. This process is the most difficult for large companies to do while they are running their core business. The risks involved and the long horizons for seeing returns are often something large companies do not have an appetite for.

The Three Horizons

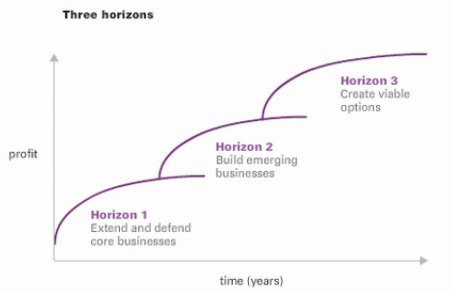

The Innovation Ambition matrix is similar to the three horizons framework from McKinsey. Featured in the seminal book The Alchemy of Growth, this framework provide a lens through which companies can manage for future growth without killing their core products.

- Horizon One represents the core businesses and products that are currently providing profits and cash flow. This is similar to core innovation since the focus is on optimizing the performance of the current business models in order to maximize revenue, profits and investment returns.

- Horizon Two focuses on emerging opportunities that are likely to generate sustainable profits in the near future. Similar to adjacent innovation, the product/services may require some investment but the levels of risk are no longer as substantial. Since these are relatively safe bets, investment in growing these opportunities will very likely generate substantial new revenues for the company.

- Horizon Three focuses on ground-breaking ideas that may result in profitable growth in the future. These are the ‘crazy plays’ that are bets on future trends and emerging technologies. This is similar to transformational innovation in that the company is thinking about new products for new markets. As such, they could invest in R&D projects, innovation labs or even take stakes in emerging startups.

The point of these frameworks is to illustrate how an established company should view or examine its portfolio of products. It is important that a company has products that cover the three horizons and the three types of innovation. If a portfolio only has core products, then that company is not geared up to be adaptive to changes in its environment. But before I proceed to a discussion about what balanced portfolios look like, I would like to first examine Christensen’s notion of disruptive innovation and how it relates to the two frameworks presented so far.

Disruptive Innovation

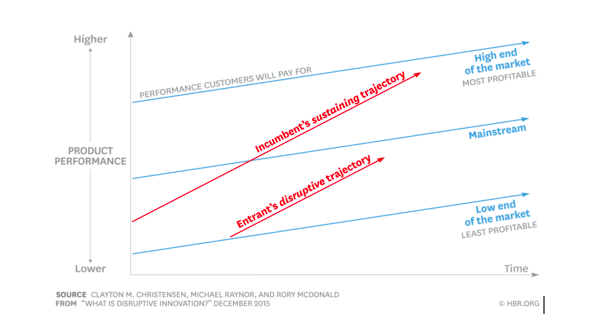

Disruptive innovation, as distinct from sustaining innovation, was first introduced by Clay Christensen in his best-selling book, The Innovator’s Dilemma. Since then, the term ‘disruption’ has been commonly used to describe any situation in which a large incumbent company is replaced by a startup. However, this usage is pretty broad and not representative of Christensen’s original thinking. It is also important to highlight that the sustaining versus disruptive innovation distinction is different from the three types of innovation I have described above. There two types of disruption that can happen to large incumbents.

The first type is referred to as low-end foothold disruption. This describes a situation in which smaller companies enter markets by first targeting overlooked lower-end market segments and delivering products with more suitable functionality, often at cheaper prices. This happens because large companies tend to focus on their most profitable customers by providing ever-improving products and services; and simultaneously pay less attention to their least profitable customers. However, in doing this they end up with products that provide functionality that is well beyond the affordability and needs of the lower end of the market. This opens up an opportunity for new entrants to enter the market at the low-end.

The second type is referred to as new-market foothold disruption. In this situation, new entrants start by focusing on new or emerging market segments that are currently too small for large companies to pay attention to or care about. This often happens through a focus on non-consumption (i.e. they successfully turn non-consumers into consumers). The technology serving these nascent markets (and low-end markets) is often still rudimentary and not to the standard that mainstream customers would appreciate. A classic example is the Apple 1, which was very rudimentary but also targeted an emerging market of personal computer enthusiasts.

In the meantime, large incumbent companies ignore the new entrants and continue to focus on improving their products and services for their most profitable customers. This activity is what Christensen refers to as sustaining innovation. These business decisions make short-term sense in terms revenues and profits but in the long-term they also create challenges. This is because, while large companies are focusing on meeting the needs of their most profitable customers, the new entrants continue to improve their products and eventually start to move upmarket.

As the new entrants move further upmarket, they have an advantage in that they can preserve their lower cost-structures and the customers that made them successful at the lower end of the market. Eventually the new entrants will start delivering product performance that attracts the more profitable customers of the large incumbent companies. When the customers of the large incumbent companies start buying the new entrants’ products and services, disruption is said to have occurred. This illustrates that disruption is process, not a sudden event. It is true that the process can happen quickly or take years, but understanding how it happens can help companies as they think about how to manage the three horizons of innovation.

Highlighting the distinction between disruptive innovation and the other types of innovation is not mere theoretical nitpicking. I feel that in order to develop a balanced portfolio, large companies need not only consider the three horizons of innovation. When thinking about their innovation strategies, they also need to be conscious about the how much of their work is focused on low-end and nascent markets. The lower profits and higher risks in these markets may lead large companies to ignore or avoid them, even as they are working across the three horizons of innovation. A focus on disruption directs managers to look in places they would not normally look.

A Balanced Portfolio

Understanding the different types of innovation is also important because it has practical effects on how managers view their role with regards to their product portfolio. These distinctions provide companies with a language and taxonomy that they can use in a consistent way within the company. Using the same language means that managers and teams can easily communicate about products and services, where they sit within the portfolio and what needs to happen with them. However, the ultimate goal of these innovation frameworks is to help companies create an ecosystems of products, services and business models that can be regarded as a balanced portfolio.

A balanced portfolio is one in which a company has products and services that cover all three horizons of innovation. McKinsey strongly recommend that companies should manage all three horizons concurrently. If the management of horizons is done in a linear fashion, the company might end up facing a crisis before they even get to the second horizon! The only way to guarantee that the company is being run with short-term, medium-term and long-term goals is to manage the three horizons concurrently.

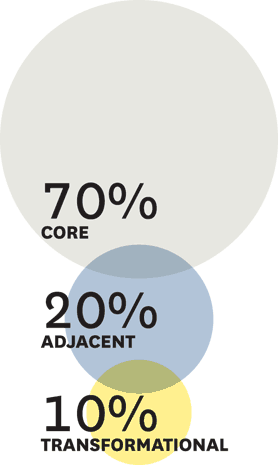

Nagji and Tuff propose a “magic formula” of 70–20–10 that companies can use to balance their portfolios. They recommend that companies should invest 70% of their resources into core innovation, 20% into adjacent innovation and 10% into transformational innovation. This is what they refer to as a balanced portfolio.

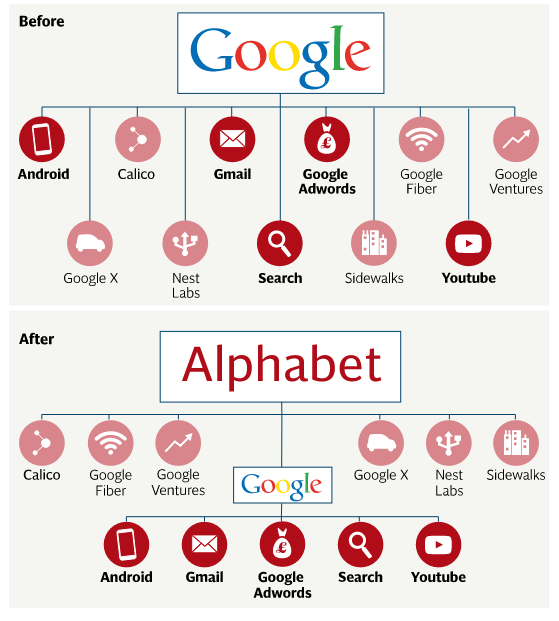

Google is an impressive company when it comes to building an innovation portfolio. Over the years Google has expanded the range of its products to go beyond just their search engine which is a massive cash cow product. Based on their innovation thesis of betting on technical insights, Google has launched or acquired a wide range of products and services including GMail, Google Maps, iGoogle, Youtube and Android. The company has even bet on physical products by acquiring Motorola, working on self-driving cars and launching Google Glass. Not all of Google’s bets have succeeded (e.g. Google Wave), but they have a had quite a few successes

Google’s innovation ecosystem was fully instantiated when it transformed itself into the holding company Alphabet on August 10th, 2015. Alphabet became the parent company to Google and various other divisions including Nest Labs (smart home products), Google Fiber (high speed internet) and Google Venture (growth stage investing). Looking at the new structure it is clear that the rest of Alphabet represents bets on the industries of the future, whereas Google is the part of the business that pays the bills for now. My suggestion is not that every company should transform itself into an “Alphabet”. However, every company should strive to have a balanced portfolio that contains some bets on its future sustainability.

For Google, this aspiration is clear in the statement below from Larry Page’s letter to the market at the launching of Alphabet:

“We’ve long believed that over time companies tend to get comfortable doing the same thing, just making incremental changes. But in the technology industry, where revolutionary ideas drive the next big growth areas, you need to be a bit uncomfortable to stay relevant” — Larry Page CEO Alphabet Inc.

Just like Google, Facebook is also building its innovation portfolio. At the F8 conference in April 2016, Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg announced the company’s ten year roadmap. The roadmap was divided into three sections, which represent the three horizons of innovation. The first three years are focused on improving Facebook as an ecosystem; the next five years are focused on strengthening products such as WhatsApp and Instagram; and the ten year horizon includes technologies such as artificial intelligence and virtual reality. This third horizon is a bet on emerging technologies in nascent markets. If this roadmap is well executed, it will move Facebook away from an exclusive focus on its core product; and also allow the company to move into the future in a sustainable way.

Considering Disruption

In building an innovation portfolio, we must be mindful of disruption from low-end or emerging markets. When we do our business environment analysis, a question must always be asked about how much of our portfolio is focused on tackling potential disruption from low-end or new-market competitors. What the company must resist at all costs is the natural reaction to walk away from the apparent low profit margins and revenues that currently define these markets. Low-end and new-market competitors can grow quickly and take away market share.

An innovation portfolio is not properly balanced until it covers the three types of innovation, while simultaneously considering disruptive innovation. How a company does this will be determined by its overall strategy, context and innovation thesis. However, there are frames of reference that the company can use. For example, when considering transformational innovation, the company should examine emerging technologies and nascent markets. On the other hand, with adjacent innovation a clear option is to develop versions of our core products that can be taken into low-end markets.

A great example of this is Intel’s creation of the Celeron processor. As a highly innovative company, Intel has historically pushed the envelope in designing faster and better processors for computers and other devices (e.g. Intel Core i7–4770K). However, after reading and hearing about Christensen’s work in 1997, Andy Grove who was at the time CEO of Intel called in Christensen for a meeting. After listening to Christensen talk, Grove rightly concluded that in addition to the pursuit of better and faster processors, Intel should also create their own low-end products. This gave birth to the highly successful Intel Celeron processor. This collaboration between Groves and Christensen is celebrated as a great example of a company protecting itself from disruption by new entrants that were entering the market from the bottom.

Epilogue

It is not an option for an established business in the 21st century to not have a balanced portfolio. Business schools used to teach managers to pick a generic strategy such cost leadership, build their business around that and then protect their competitive advantage. Nowadays, such an approach is no longer adaptive. The balanced portfolio approach is becoming the new norm. This not only requires an ecosystem of products and services under one business model, a properly balanced portfolio has to have different business models within it. Knowing how to do this is now Management 101. In other words, executives are not doing their jobs if they are running companies that don’t have balanced portfolios.

______________________

Thanks to everyone who gave their feedback to this earlier version of the article. This work will be part of a book that we are currently writing called The Corporate Startup. Please sign-up for updates here.