In a previous post on this topic, I argued that large companies are not startups, nor should they strive to be. My argument was based on the reality that, unlike startups, large companies tend to have products and services that are already successful in the marketplace. As Steve Blank puts it, the distinction between startups and large companies lies in the fact that startups are still searching for a profitable business model, whereas large companies are mostly executing on an already successful business model.

As such, in order to succeed, large companies should not be acting like startups. Every startup’s aspiration is to become a successful company! So abandoning business model execution practices and applying searching methods on an already successful business model is a form of waste. I strongly believe that operational excellence is still an important management practice, even in times of rampant disruption. Our cash cow products are how we get the money to invest in innovation.

The argument I am making here is NOT that large companies should ignore startups or the changes that are happening in their business environment. Innovation is now an imperative. Large companies must innovate or die. I am arguing that large companies should not see themselves, or act as if they are single monolithic institutions with a single business model. If they view themselves as one single company with one business model, then the false choice of acting or not acting like a startup becomes ‘real’.

The best way to innovate is for a large company to view itself as an innovation ecosystem with various products, services and business models. From this perspective, it is then possible for the large company to decide which of its products have validated business models and are in execution mode and which of its products are still in startup or search mode. This is how a company becomes an ambidextrous organization that is, in practice, excellent at both searching and executing.

A Balanced Portfolio

The first step in creating an innovation ecosystem is to have a balanced portfolio of products and services. It is not possible to search for new business models if your product portfolio only comprises of established core products. Important as they are, in financial terms, the entire focus of the organization cannot simply be on core product optimizations.

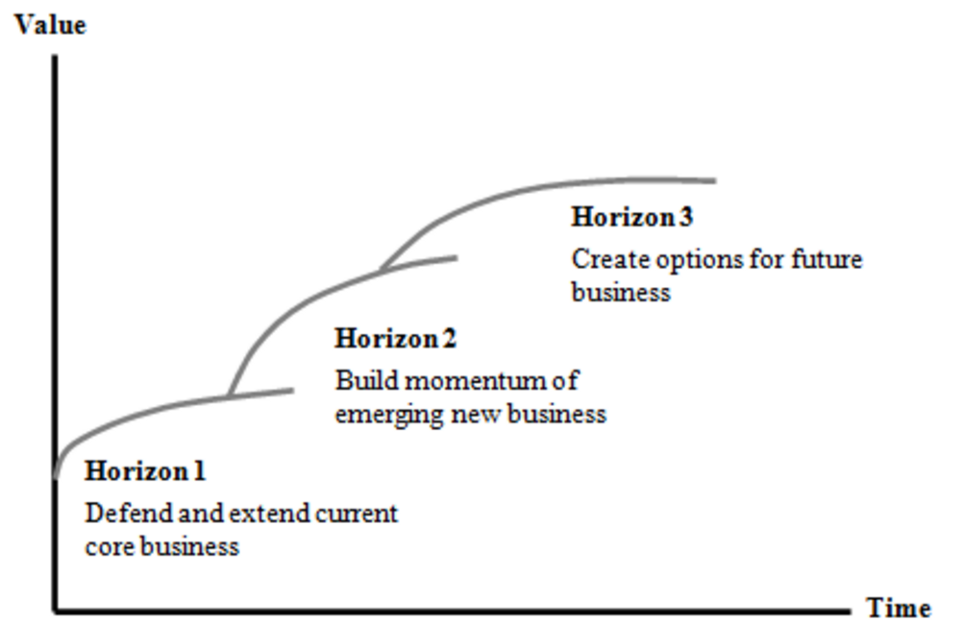

A great framework to use for innovation ecosystem design is McKinsey’s three horizons framework. This framework helps companies to focus on innovation without neglecting the performance of currently successful products and services:

- Horizon One focuses on the core business and the products that a currently providing the greatest profits and cash flow. For these products, the focus is on optimizing performance and maximizing revenues and profits.

- Horizon Two focuses on emerging opportunities that very likely to generate substantial profits in the future. These opportunities are likely to have already been tested and the company feels confident to invest in their future success.

- Horizon Three is the startup end of the spectrum. This contains the ‘crazy bets’ that the company is making for potential profitable growth down the road.

A similar framework, which I use most often in my work is Nagji and Tuff’s Innovation Ambition Matrix. This framework provides a great lens through which a company can balance its portfolio of products and services. It is based on two main dimensions; new products versus existing products and new markets versus existing markets. It is a redesign of the famous Ansoff Matrix. On the basis of these two dimensions they distinguish three types of innovation which are: core, adjacent and transformational.

- Core Innovation efforts focus on making incremental changes to existing products for existing customers. This can be in the form of new packaging, small redesigns of products or improvements in service. The important thing here is that these innovations draw on assets the company already has in place and customers that they already understand well.

- Adjacent Innovation involves taking something the company currently does well and applying it to new markets or the development of new products and services. The point here is that the company is drawing on existing capabilities and putting them to new uses.

- Transformational Innovation focuses on creating new offerings for new markets. This double-whammy of new product and new markets means that the company has to develop new capabilities while simultaneously testing these offerings in the target new markets. This is the startup edge of the matrix.

Both the three horizons framework and the innovation ambition matrix provide a great lens for evaluating the investments a company is currently making in its product portfolio. In the typical unbalanced portfolio almost all of a company’s products are horizon 1 or core products. This is a company that is not making bets on the future. Instead this company is betting that its current crop of products will sustain its growth and survival over the long term. As we know, these are the wrong bets to be making.

A balanced portfolio is one in which a company has products under each one of the above innovation categories. Nagji and Tuff researched several companies and came up with a “magic formula” that can be used by companies that are keen to balance their portfolio, 70–20–10. This formula proposes that 70% of investments should be made in core innovation, 20% in adjacent innovation and 10% in transformational innovation.

This magic formula is not uniform across industries. It can change on the basis of industry norms. For example, the ratio for consumer goods companies is 80–18–2; whereas the ratio for mid-stage technology firms in 45–40–15. Even with these norms in place, a company can decide its own ratios based on its strategic goals. The point is to make explicit what you innovation ambitions are. Without this explicit decision, it becomes hard to be consistent about creating an innovation ecosystem.

Managing The Ecosystem

But here is an important takeaway: it’s not only important to have a balanced portfolio of products and services, it is also important to understand that the way a company manages core innovation is different from the way they manage adjacent and transformational innovation. This difference is based on the number of risky assumptions you have. These risks move from known customers with known needs for core innovation — to unknown customers with unknown needs for transformation innovation.

Core innovation is in many ways similar to execution, which can mostly be managed using traditional methods and metrics such as profits, ROI, NPV and ARR. In contrast, adjacent and transformational innovation involve differing levels of searching. Transformation innovation, in particular, requires people who are comfortable with ambiguity and investment processes that are comfortable with experimentation and iteration. It is also important for the company to create process for integrating successful innovations back into the core product portfolio.

People who tell large companies to act like startups are giving them the wrong advice. Instead, the advice should be that large companies must own innovation ecosystems that contain core products as well as transformational or startup type products and services. This is a more nuanced approach that recognizes the unique situation that most large companies are in. The key question now is, what is the balance of the portfolio within your business?

_______________________________

This article was first posted at www.tendayiviki.com.