Much has been written about the changing landscape in the business of education. Christensen’s Disrupting Class is a great book, so is Kevin Carey’s The End of College: Creating the Future of Learning and the University of Everywhere. There are also several articles highlighting the increasing investments in the EdTech space which have grown over 503% in the last five years; and the rising startups that are disrupting education as shown in the image above.

There is some debate as to whether the coming disruption of education is greatly exaggerated. This article will not wade into that debate. Instead, this piece is a cautionary note to the large incumbent companies in the education industry about what disruption might look like when it is happening. The theme here is to caution that it is not badly run companies that get disrupted, but well run companies that are making sensible management decisions, given their business and where they are.

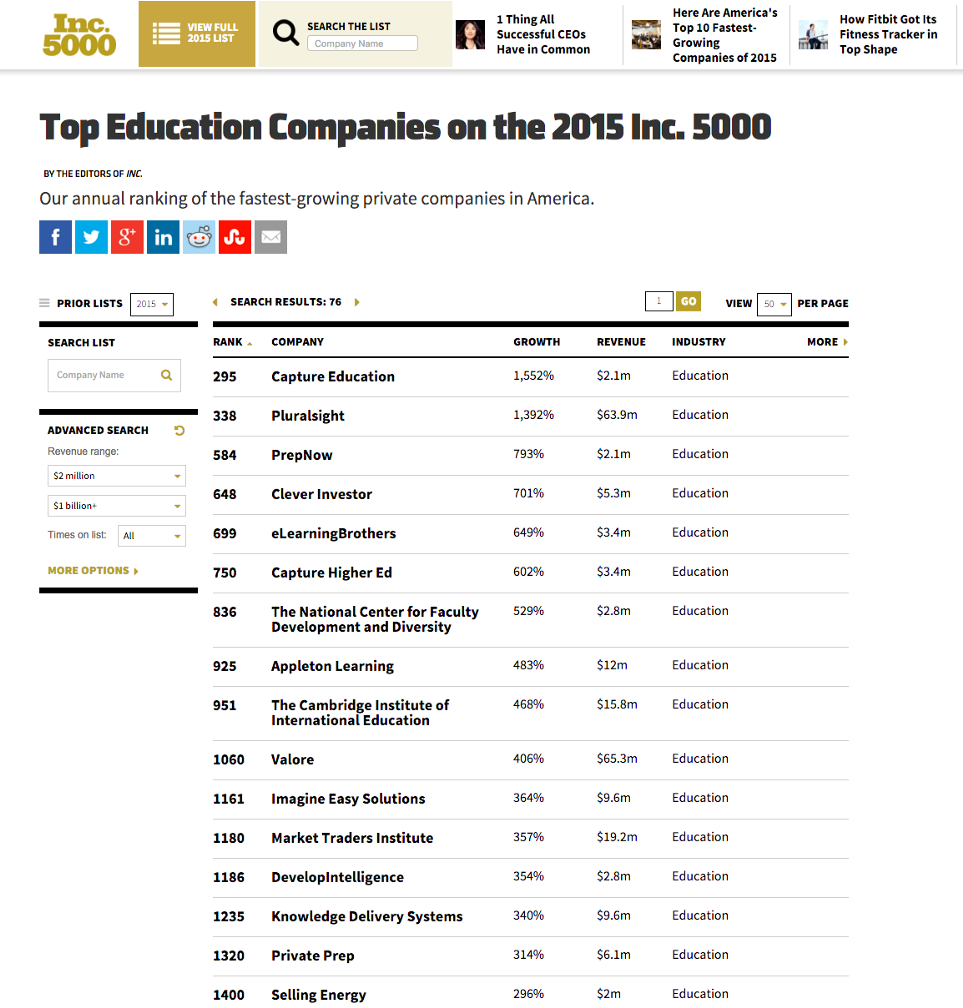

The Top 50 Fastest Growing Education Companies

Recently, Inc. Magazine published their annual top 5000 fastest growing companies in the United States in 2015. Of those, they have a list of the top 50 fastest growing education companies. The growth rates are fascinating, with some companies growing by as much as 1552%. Even the slowest growing education company still had an impressive 87% growth rate. The average growth rate across the companies was 301%.

But these growth rates are not where we will find the hidden gems of disruption. This secret to disruption is hiding in the revenue numbers that the companies posted. The fastest growing company Capture Education only posted revenues of $2.1 million. The highest revenue numbers were posted by Curriculum Associates at $83.5 million. In fact, 37 of the top 50 companies all had revenue of less than $10 million. The average revenues for the top 50 were $10.81 million.

These small revenue numbers is where the danger lies for large companies. When you are multi-billion dollar juggernaut, why should you care about a little startup somewhere that has only $2.1 million in revenue. If your company added this revenue to its bottom line it wouldn’t even tip the scales of the growth rate you require to meet your obligations to the market and shareholders.

This takes us to Christensen’s second principle of disruption: Small (emerging) markets don’t solve the growth needs of large companies. While a $20 million dollar company needs to find only $2 million in new revenue to grow 10%; a $5 billion dollar company needs a whopping $500 million in new revenue to grow at a similar rate. As such, it makes management sense to dismiss $2 million dollar ideas because they will not meet the short term growth needs of a large company. For management in large companies, it makes more sense to pursue reliable sources of large revenues.

This is why disruption happens. The above decisions are made with the best intentions driven by management best practices that fit the needs of a large company’s position in the market. However, with the trends in technology being what they are, small companies can now be sustainably profitable with small amounts of revenue. Furthermore, these companies will keep growing and taking away small bits of market share from large incumbents.

But here is the scary part. If you add up the revenue of the top 50 education companies, it totals $540 million. This number matches exactly the $500 million that is needed for a $5 billion dollar company to grow 10%. However, this number is now distributed over 50 companies, all potentially profitable in their small niches over the next 3 years; because they have a lower cost base than large incumbent companies.

It is death by a thousand cuts. Or in this case 50 cuts! Disruption happens because of the sensible tendency by management in large companies to dismiss emerging startups due to their size. Many large companies will wait until emerging markets become large enough to be interesting for their growth needs. But Christensen’s work shows that this strategy of ‘wait and see’ is a key ingredient in the recipe for disruption.

Large companies will also wait until some of the startups are successful or interesting enough to acquire. This might work, but it is an expensive way to do business. And you can’t buy all 50! If the companies are successful they have the option to refuse a sale and pursue their growth strategies.

Small companies can mostly easily respond to the market needs of small emerging markets. After all they don’t need that much revenue. Large incumbents are trapped by their growth needs which are based on market expectations. The challenge is for large incumbents to fight the instinct to ignore and dismiss small opportunities. This is the innovator’s dilemma. It is those very same small opportunities that will eventually “eat your lunch”.

Every large company should have a portfolio of products that includes the core business with its large revenues, and loads of little bets it is making in the so-called ‘small markets’ that have the potential to be disruptive. This is a balanced portfolio that helps the company meet both its short-term and long-term growth needs.

__________________________

This article was first posted at www.bennelijacobs.com.